With Prometheus about to enter theaters, you may have been one of many—myself included—who put “watch Alien” on their to-do list. Director Ridley Scott and writer Damon Lindelof have tried to obscure the relationship between this summer’s blockbuster and the 1979 classic, but the former is a convenient excuse for visiting the latter.

Alien is one of the most important sci-fi films ever made. Forget about all the Alien vs. Predator garbage and the commercialization of the franchise that occurred in the ‘90s (I had a couple plastic Xenomorphs back in my day), as that misrepresents its origins completely. Instead, consider the style and tone of the film.

The films that really started the ‘70s sci-fi revolution are most obviously Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind in 1977, but Alien came just two years later, no doubt standing on the shoulders of those films, even if its biggest inspiration has to be Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Scott’s treatment of outer space echoes “2001” in its minimalism—the quiet, brooding solitude of space. Whereas Star Wars and Star Trek turned space into a twinkly playground of imagination, Alien treats its more imaginative aspects naturally. Swiss artist H.R. Giger, who won the Best Visual Effects Oscar for his work on the film, designed a lot of iconic visuals for the movie, yet they serve as scope more than spectacle. The Space Jockey has literally nothing to do with the film (we’ll see what Prometheus has to say about that), yet it is one of the more lasting images from the movie. Without it, Alien is just a horror movie in space.

Not that there’s anything wrong with considering Alien just a horror movie in space. In fact, I think that’s its most powerful contribution to cinema. Horror films are about atmosphere, and what better atmosphere than a cold and lonely black void somewhere far, far away? Alien merged these genres in a way that created the realization that the genres are not exclusive, nor do they have to be Ed Wood-type B movies.

Scott was also forced to make due with the money 20th Century Fox gave him. When you talk science fiction at studios these days, their gut reaction is going to be budget concerns. Sci fi has become associated with spectacle, whereas Alien is the great fortress erected at the opposite end of the spectrum. Alien is still one of the few classic and loved sci-fi films to operate at a lower production cost. The final budget was $8.4 million (twice its initial size), which equates to just short of $30 million these days.

The handling of the Alien itself (a.k.a the xenomorph) also created a blueprint for handling monsters and aliens in the future. Scott gives us the bare minimum visually until the final scene at the end. Admittedly you can tell it’s a costume at that point, but when you first see the movie you’re so overcome by the fact that the Alien made it onto the escape craft in the first place. You never get a good look at the thing until the suspense has built up beyond the point of containment. The glimpses we do get make us curious thanks to Giger’s exceptional design. It's too bad that all the branding done to the franchise has engrained the look of the xenomorph into the minds of those young enough to have not yet seen the film.

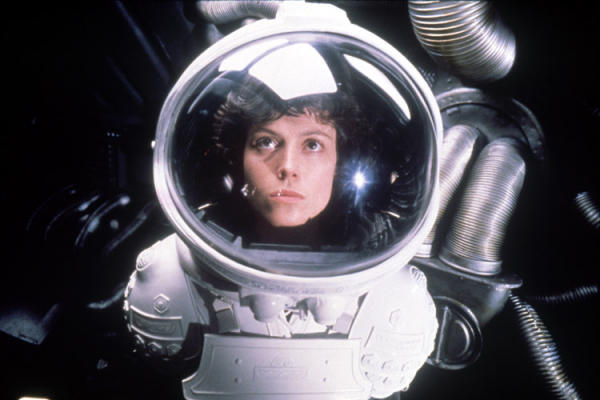

From a story perspective, Alien is simple yet effective thanks to a tremendous turn of events. The exploration of the fallen spacecraft on the nearby planetoid starts the scope off rather large, and when the crew gets back to the ship and Kane (John Hurt) has an alien stuck to his face, it slowly begins to narrow until it becomes a contained horror film. Our hero, Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) also emerges as the hero during the middle of the film. It doesn’t become her story until the end, but her willingness to act in the face of fear makes her an instant winner.

Thematically, Alien also does more than you’d ever expect. What starts as a simple debate of risking one life vs. the lives of the many evolves into a story of life vs. the pursuit of science: Ripley realizes she was never necessarily meant to return home, that the Weyland-Yutani corporation valued a live alien specimen more than the lives of her crew. It becomes a whole other fight when we realize Ash (Ian Holm) wasn’t simply following protocol by his own volition, but because he’s an android, and suddenly science has its icy grip around the fate of the Nostromo.

What ultimately makes Alien such an entertaining movie lies in appearances. There are so many points in which the film becomes something you did not expect, be it a plot device or a shift in focus. The chest-bursting scene is one of the most iconic moments in horror history because whether you know it’s coming or not, it’s still incredibly effective and jarring. The movie is never the same after that.

In the full-on blockbuster age, you appreciate a film like Alien all the more, which is why the prospect of Scott’s return with Prometheus is so appealing to fans of the original film. This is not the same as if Martin Scorsese announced a new mob project—this is the promise of some kind of intelligence making its way into the world of the epic blockbuster once again.