Why is Doctor Who a Mess Under Steven Moffat, While Sherlock Thrives?

I shamefully admit that I only recently started watching

Sherlock. Worn down by the constantly nagging of friends and family (who have all since gloated (repeatedly) at my new found love of the show and their hand in getting me to watch it), I fired up my Netflix account and started watching. And, much to my complete surprise, I was hooked.

Now, if you are a fan of

Sherlock, you are likely not surprised that I fell in love with the show. Sure, there are some issues with the series, but it is, on the whole, a completely enjoyable modern version of the Sherlock Holmes story. But let me tell you why I was so surprised that I enjoyed

Sherlock so much: it was co-created by Steven Moffat.

Who is Steven Moffat? Well, he’s a writer/producer of British television. Aside from

Sherlock, his main claim to fame is his involvement with the popular British series

Doctor Who. Or, as I tend to see him, he’s the guy who has run

Who into the ground.

This isn’t meant to be an article bashing Moffat, or harping on the reasons why his version of

Doctor Who has been so spectacularly less successful (from a creative standpoint) than the version of the show presided over by Russell T. Davies (Moffat’s immediate predecessor, who certainly wasn’t a perfect showrunner, but who managed better than Moffat has). Rather, the one question that struck me as I devoured nine episodes of

Sherlock in the span of a week was: How can

Sherlock be such an engaging and well-crafted series from a storyline perspective, while

Who so often turns into a jumbled mess?

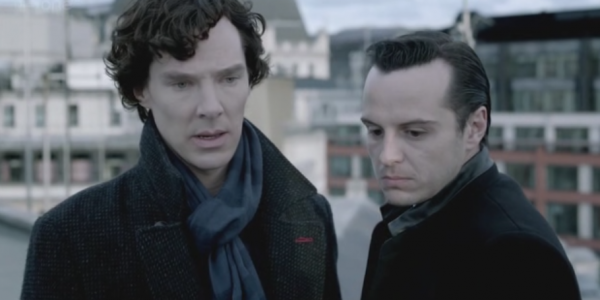

I don’t feel that it is a question of casting (while both Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman have been catapulted into amazingly successful careers as the result of their work on

Sherlock, both Matt Smith and Karen Gillan- the first two “stars” of the Moffat era of

Who- are both poised for success with major films and stage roles set for this year), and both shows come complete with built in fan bases, so it’s not an issue of the original source material.

After much thought, I came up with three distinct elements that account for the distinct difference in quality- all three of which lead back to Steven Moffat and his involvement in each project.

1.

Steven Moffat has a problem creating and maintaining female characters.

I remember reading Hemingway’s

A Farewell to Arms in high school and being pretty put off that the book’s most prominent female character was pretty worthless and devoid of personality and drive. She was, as my English teacher Br. Ruhl told our class, a “lollipop,” simply a head on a stick- all sugar and no substance. Now, Moffat’s female characters aren’t quite as bad as this. They are usually well-spoken, can challenge the series’ male lead, and are self-sufficient – to a point.

In general, a female character on both

Sherlock and

Who appears on the surface to be a foil for the series’ central male character. In the great tradition of

Doctor Who (or, at least, in the recent tradition of the series’ modern revival), the Doctor traverses time and space with a female companion, who is meant to be the audience surrogate (experiencing the amazement, joy, and pain the audience feels in regard to whichever adventure is on tap for that particular week).

During the Davies years, the female companion played multiple roles alongside the Doctor- possible love interest, capable young woman with a bit of a crush on the Doctor, and a great pal for a man without many friends. On the whole, each companion had at least one time wherein she saved the Doctor from something, whether it be death or his own hubris getting in the way of saving others. But we knew that Rose, Martha (who was the weakest of these three from a story perspective), and Donna could hold their own and save themselves should it become necessary (the fourth season episode “Turn Left” is an excellent example of this).

Once Moffat took the reins, the era of the fully realized female companion disappeared. Amy Pond was a character defined almost completely by her relationships with the two men in her life (Rory and the Doctor). She constantly needed the Doctor to save her from something, even her own future self. And Clara, the most recent companion, had her entire initial storyline built upon the premise that she was a puzzle for the Doctor to solve. She’s a smart and spunky young woman, but she’s the one that needs the Doctor, not the other way around. And when a series is built on the idea that your central character needs these companions to make sure he doesn’t lose his own sense of self (be it losing his sense of wonder or preventing him from taking steps to destroy a civilization), having a companion who contributes little more than being a person to bounce ideas off of is troubling.

Now,

Sherlock isn’t particularly great with its female characters, but it doesn’t matter nearly as much as with

Who. Unlike

Doctor Who,

Sherlock is about the relationship between Sherlock and Watson (Cumberbatch and Freeman). When your female characters are relegated to one-off guest appearances or supporting characters, there’s less of an emphasis and a need to write truly compelling storylines for them. And, used in this way, Moffat appears to have a fairly good grasp over how to effectively utilize the women that dot the

Sherlock canvas.

The only time I’ve been disappointed with a particular female character on the series (or, at least, noticed enough about a character to be disappointed) was with Irene Adler, who started off as such a compelling and interesting character and rapidly dissolved into a true damsel in distress for Sherlock to save (unsurprisingly, very similar to Moffat’s most notable female

Who creation River Song). Now, some of this is due to her literary origins and the conceit of the series (that Sherlock has to be the smartest one in the room), but it was still a disappointment.

The addition of Mary (the new wife of John Watson) to

Sherlock has been a lovely surprise, as she appears to be defying the odds and turning into a complex and layered character. Without giving too much of her story arc away for those who have yet to watch the third series, there is certainly hope that Mary will continue to break the mold of a traditional Moffat female character. But, seeing how well-crafted Mary appears to be just makes the failure of

Who to give us a complex female character all the more mind-boggling.

So, save for Mary (and the jury is still out on her), as long as the female characters are relegated to the background or only pop up once in a great while (Madame Vestra and Jenny on

Doctor Who, for example), Moffat can craft perfectly fine characters. Which, in turn, allows a series like

Sherlock to only occasionally feel the strain of his inability to write for female characters, while a series like

Who, which relies on a central female character to work alongside the male lead, suffers the consequences.

2.

Moffat cannot successfully sustain a long story arc.

One of the most infuriating things about

Sherlock is that a season only lasts three measly episodes. And, considering the rising stars of Cumberbatch and Freeman, who knows how much time the pair will have in the future to devote to season four. But, when looking at Moffat’s track record with

Doctor Who, and its significantly longer seasons, perhaps

Sherlock fans should look on the shortened length their show’s season as a blessing.

Both

Who and

Sherlock operate in similar manners. Each contains a set of stand-alone episodes that coalesce under the banner of a longer arc. While this works excellently with

Sherlock, having the final season end game hinted at over the course of the three episodes (or, sometimes having it revealed in the season finale that a particular character has had his or her hand in things for some time), with

Who, each arc sputters along in a bit of a muddled mess with the writers seeming to make up the rules as it goes along.

Now, I certainly believe that Moffat sits down and charts an arc for

Doctor Who at the start of each season. After all, not to do so on a series that involves traversing time and space would be pretty foolish. And while viewers don’t want to see each minute beat of the arc played out clearly on screen (as it makes things rather tedious), they also don’t want major jumps in the story, coupled with characters simply explaining away the missing pieces. Even if your show deals with time travel, you don’t get a pass on showing the audience how events unfold.

When watching a season of

Sherlock, you can sit back at the end of the finale and piece together the major season arc (and, at the end of each episode you can do the same with the episode arc). It’s not so clearly telegraphed that you can anticipate what’s to come (a frequent pitfall in a mystery), but there are enough threads to tie the story back together. It’s smart and well-constructed storytelling.

When watching

Who, you can get to the end of a season and have no real understanding of what actually happened. I’m still trying to piece together everything that we found out about Clara and her moniker as the “Impossible Girl” (not to mention how the 50

th Anniversary Special- as good as it was- failed to actually link to the previous episode in any way aside from showing us the War Doctor). Too often, the show relies on the nature of time travel to explain away inconsistencies (or, simply ignore anything that might be true about time travel to allow other event to happen). It’s sloppy and often lazy storytelling.

If Moffat is constructing a limited arc for

Who, it is often excellent (see the “Silence in the Library” storyline as an example of a wonderful, but brief, arc). But when he is called upon to put together an arc over 10 or more episodes, the story falls apart and becomes embroiled in broken story threads and confusing story jumps. With Moffat, less is most certainly more.

3.

Moffat needs a co-showrunner.

This is the most important of the three elements I came up with when pondering the success of

Sherlock versus the disappointment of

Who. On

Sherlock, Moffat works alongside co-creator Mark Gatiss (who also portrays Mycroft Holmes on the series), while Moffat has spent most of his tenure as the sole showrunner for

Who (there have been additional executive producers on the show during this time, but Moffat has been the true showrunner).

Now, it’s a herculean task to be a showrunner of one show, much less have two under your control (even if one only films every other year), so I do have sympathy for the massive undertaking Moffat is attempting. But, that doesn’t mean that I can excuse how poorly

Who has fared during his time at the helm.

When Moffat speaks of his work crafting the story arcs for

Sherlock, he discusses how he and Gatiss sit together to create the stories. The collaborative aspect of such a set-up almost certainly fosters the stronger storylines while allowing for the dismissal of the weaker options. While there is a team of writers working on

Who, Moffat is charged with being the central voice in crafting the season long arcs and assigning the individual episodes to the writing staff. Being responsible for arcs of ten or more episodes each year is a great amount of content to craft and a great deal of story for one person to be in charge of.

Having a writing partner (it should be noted that Moffat and Gatiss are the sole authors or co-writers of every

Sherlock episode) undoubtedly makes putting together a complex series like

Sherlock leagues easier than it would be alone. With a producing partner alongside you every step of the way, each idea is vetted by someone with the same ranking in the production. Presumably, there have been disastrous

Sherlock ideas that have fallen by the wayside due, in part, to the roles Gatiss and Moffat play in the writing process.

With

Who, Moffat is ostensibly the final creative word on the story. The writers create the individual scripts (Moffat only occasionally writes

Who episodes now), and pass them onto Moffat for a final pass. Now, I could be off base, and there might be a major meeting on every script to discuss the storyline and how the particular episode features into the larger season arc. However, the

Who writing process has been detailed in several interviews as having a script assigned to a writer, who writes it and turns it in to Moffat (unlike in many US productions, there isn’t a true “writers’ room” where stories are “broken” with the entire writing staff present).

Now, one might ask, why is this such an issue for the Moffat era of

Who? After all, Russell T. Davies operated with a similar set-up when he ran

Who. I think the major difference is in Moffat’s past television experience (or, lack thereof). Davies had been the showrunner for the British version of

Queer as Folk prior to launching

Who, so he had past experience running a popular and complex series. Moffat, while having previous television experience, didn’t have that same background.

No matter what the reasoning behind Moffat’s inability to successfully manage a television series on his own, it is clear that when he is teamed with a co-showrunner, the show runs smoothly.

Sherlock’s success is the result of many elements working well together, but at its heart is the strong storylines and great writing- all attributable to the collaboration between Moffat and Gatiss.

Having explored these three elements, there is most certainly hope that

Who can rebound into a series that is similar in quality to

Sherlock. While shortening the

Who season is absolutely not going to happen (and, honestly, it shouldn’t have to happen- plenty of shows are able to sustain a complex narrative over the span of 10-13 episodes), there have been rumors regarding the BBC bringing in a co-showrunner for the series. As for the issue of Moffat’s lost female characters, with the advent of Mary on

Sherlock, it’s become clear that Moffat (when combined with Gatiss) is able to produce an interesting, complex, and self-sufficient female character who doesn’t need a man to survive in the world.

I’m not entirely sure

Who will truly be able to rebound under the control of Moffat (reports have indicated that he may be looking to step down from the show after this upcoming season). But I remain hopeful that positive steps can and will be taken to make it more watchable. But, until I see that change, I will continue to warn

Sherlock fans away from the recent seasons of

Who, while continuing my recent campaign to get everyone I know to watch

Sherlock.

This isn’t meant to be an article bashing Moffat, or harping on the reasons why his version of Doctor Who has been so spectacularly less successful (from a creative standpoint) than the version of the show presided over by Russell T. Davies (Moffat’s immediate predecessor, who certainly wasn’t a perfect showrunner, but who managed better than Moffat has). Rather, the one question that struck me as I devoured nine episodes of Sherlock in the span of a week was: How can Sherlock be such an engaging and well-crafted series from a storyline perspective, while Who so often turns into a jumbled mess?

I don’t feel that it is a question of casting (while both Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman have been catapulted into amazingly successful careers as the result of their work on Sherlock, both Matt Smith and Karen Gillan- the first two “stars” of the Moffat era of Who- are both poised for success with major films and stage roles set for this year), and both shows come complete with built in fan bases, so it’s not an issue of the original source material.

After much thought, I came up with three distinct elements that account for the distinct difference in quality- all three of which lead back to Steven Moffat and his involvement in each project.

This isn’t meant to be an article bashing Moffat, or harping on the reasons why his version of Doctor Who has been so spectacularly less successful (from a creative standpoint) than the version of the show presided over by Russell T. Davies (Moffat’s immediate predecessor, who certainly wasn’t a perfect showrunner, but who managed better than Moffat has). Rather, the one question that struck me as I devoured nine episodes of Sherlock in the span of a week was: How can Sherlock be such an engaging and well-crafted series from a storyline perspective, while Who so often turns into a jumbled mess?

I don’t feel that it is a question of casting (while both Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman have been catapulted into amazingly successful careers as the result of their work on Sherlock, both Matt Smith and Karen Gillan- the first two “stars” of the Moffat era of Who- are both poised for success with major films and stage roles set for this year), and both shows come complete with built in fan bases, so it’s not an issue of the original source material.

After much thought, I came up with three distinct elements that account for the distinct difference in quality- all three of which lead back to Steven Moffat and his involvement in each project.

1. Steven Moffat has a problem creating and maintaining female characters.

I remember reading Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms in high school and being pretty put off that the book’s most prominent female character was pretty worthless and devoid of personality and drive. She was, as my English teacher Br. Ruhl told our class, a “lollipop,” simply a head on a stick- all sugar and no substance. Now, Moffat’s female characters aren’t quite as bad as this. They are usually well-spoken, can challenge the series’ male lead, and are self-sufficient – to a point.

In general, a female character on both Sherlock and Who appears on the surface to be a foil for the series’ central male character. In the great tradition of Doctor Who (or, at least, in the recent tradition of the series’ modern revival), the Doctor traverses time and space with a female companion, who is meant to be the audience surrogate (experiencing the amazement, joy, and pain the audience feels in regard to whichever adventure is on tap for that particular week).

During the Davies years, the female companion played multiple roles alongside the Doctor- possible love interest, capable young woman with a bit of a crush on the Doctor, and a great pal for a man without many friends. On the whole, each companion had at least one time wherein she saved the Doctor from something, whether it be death or his own hubris getting in the way of saving others. But we knew that Rose, Martha (who was the weakest of these three from a story perspective), and Donna could hold their own and save themselves should it become necessary (the fourth season episode “Turn Left” is an excellent example of this).

1. Steven Moffat has a problem creating and maintaining female characters.

I remember reading Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms in high school and being pretty put off that the book’s most prominent female character was pretty worthless and devoid of personality and drive. She was, as my English teacher Br. Ruhl told our class, a “lollipop,” simply a head on a stick- all sugar and no substance. Now, Moffat’s female characters aren’t quite as bad as this. They are usually well-spoken, can challenge the series’ male lead, and are self-sufficient – to a point.

In general, a female character on both Sherlock and Who appears on the surface to be a foil for the series’ central male character. In the great tradition of Doctor Who (or, at least, in the recent tradition of the series’ modern revival), the Doctor traverses time and space with a female companion, who is meant to be the audience surrogate (experiencing the amazement, joy, and pain the audience feels in regard to whichever adventure is on tap for that particular week).

During the Davies years, the female companion played multiple roles alongside the Doctor- possible love interest, capable young woman with a bit of a crush on the Doctor, and a great pal for a man without many friends. On the whole, each companion had at least one time wherein she saved the Doctor from something, whether it be death or his own hubris getting in the way of saving others. But we knew that Rose, Martha (who was the weakest of these three from a story perspective), and Donna could hold their own and save themselves should it become necessary (the fourth season episode “Turn Left” is an excellent example of this).

Once Moffat took the reins, the era of the fully realized female companion disappeared. Amy Pond was a character defined almost completely by her relationships with the two men in her life (Rory and the Doctor). She constantly needed the Doctor to save her from something, even her own future self. And Clara, the most recent companion, had her entire initial storyline built upon the premise that she was a puzzle for the Doctor to solve. She’s a smart and spunky young woman, but she’s the one that needs the Doctor, not the other way around. And when a series is built on the idea that your central character needs these companions to make sure he doesn’t lose his own sense of self (be it losing his sense of wonder or preventing him from taking steps to destroy a civilization), having a companion who contributes little more than being a person to bounce ideas off of is troubling.

Now, Sherlock isn’t particularly great with its female characters, but it doesn’t matter nearly as much as with Who. Unlike Doctor Who, Sherlock is about the relationship between Sherlock and Watson (Cumberbatch and Freeman). When your female characters are relegated to one-off guest appearances or supporting characters, there’s less of an emphasis and a need to write truly compelling storylines for them. And, used in this way, Moffat appears to have a fairly good grasp over how to effectively utilize the women that dot the Sherlock canvas.

The only time I’ve been disappointed with a particular female character on the series (or, at least, noticed enough about a character to be disappointed) was with Irene Adler, who started off as such a compelling and interesting character and rapidly dissolved into a true damsel in distress for Sherlock to save (unsurprisingly, very similar to Moffat’s most notable female Who creation River Song). Now, some of this is due to her literary origins and the conceit of the series (that Sherlock has to be the smartest one in the room), but it was still a disappointment.

Once Moffat took the reins, the era of the fully realized female companion disappeared. Amy Pond was a character defined almost completely by her relationships with the two men in her life (Rory and the Doctor). She constantly needed the Doctor to save her from something, even her own future self. And Clara, the most recent companion, had her entire initial storyline built upon the premise that she was a puzzle for the Doctor to solve. She’s a smart and spunky young woman, but she’s the one that needs the Doctor, not the other way around. And when a series is built on the idea that your central character needs these companions to make sure he doesn’t lose his own sense of self (be it losing his sense of wonder or preventing him from taking steps to destroy a civilization), having a companion who contributes little more than being a person to bounce ideas off of is troubling.

Now, Sherlock isn’t particularly great with its female characters, but it doesn’t matter nearly as much as with Who. Unlike Doctor Who, Sherlock is about the relationship between Sherlock and Watson (Cumberbatch and Freeman). When your female characters are relegated to one-off guest appearances or supporting characters, there’s less of an emphasis and a need to write truly compelling storylines for them. And, used in this way, Moffat appears to have a fairly good grasp over how to effectively utilize the women that dot the Sherlock canvas.

The only time I’ve been disappointed with a particular female character on the series (or, at least, noticed enough about a character to be disappointed) was with Irene Adler, who started off as such a compelling and interesting character and rapidly dissolved into a true damsel in distress for Sherlock to save (unsurprisingly, very similar to Moffat’s most notable female Who creation River Song). Now, some of this is due to her literary origins and the conceit of the series (that Sherlock has to be the smartest one in the room), but it was still a disappointment.

The addition of Mary (the new wife of John Watson) to Sherlock has been a lovely surprise, as she appears to be defying the odds and turning into a complex and layered character. Without giving too much of her story arc away for those who have yet to watch the third series, there is certainly hope that Mary will continue to break the mold of a traditional Moffat female character. But, seeing how well-crafted Mary appears to be just makes the failure of Who to give us a complex female character all the more mind-boggling.

So, save for Mary (and the jury is still out on her), as long as the female characters are relegated to the background or only pop up once in a great while (Madame Vestra and Jenny on Doctor Who, for example), Moffat can craft perfectly fine characters. Which, in turn, allows a series like Sherlock to only occasionally feel the strain of his inability to write for female characters, while a series like Who, which relies on a central female character to work alongside the male lead, suffers the consequences.

The addition of Mary (the new wife of John Watson) to Sherlock has been a lovely surprise, as she appears to be defying the odds and turning into a complex and layered character. Without giving too much of her story arc away for those who have yet to watch the third series, there is certainly hope that Mary will continue to break the mold of a traditional Moffat female character. But, seeing how well-crafted Mary appears to be just makes the failure of Who to give us a complex female character all the more mind-boggling.

So, save for Mary (and the jury is still out on her), as long as the female characters are relegated to the background or only pop up once in a great while (Madame Vestra and Jenny on Doctor Who, for example), Moffat can craft perfectly fine characters. Which, in turn, allows a series like Sherlock to only occasionally feel the strain of his inability to write for female characters, while a series like Who, which relies on a central female character to work alongside the male lead, suffers the consequences.

2. Moffat cannot successfully sustain a long story arc.

One of the most infuriating things about Sherlock is that a season only lasts three measly episodes. And, considering the rising stars of Cumberbatch and Freeman, who knows how much time the pair will have in the future to devote to season four. But, when looking at Moffat’s track record with Doctor Who, and its significantly longer seasons, perhaps Sherlock fans should look on the shortened length their show’s season as a blessing.

Both Who and Sherlock operate in similar manners. Each contains a set of stand-alone episodes that coalesce under the banner of a longer arc. While this works excellently with Sherlock, having the final season end game hinted at over the course of the three episodes (or, sometimes having it revealed in the season finale that a particular character has had his or her hand in things for some time), with Who, each arc sputters along in a bit of a muddled mess with the writers seeming to make up the rules as it goes along.

Now, I certainly believe that Moffat sits down and charts an arc for Doctor Who at the start of each season. After all, not to do so on a series that involves traversing time and space would be pretty foolish. And while viewers don’t want to see each minute beat of the arc played out clearly on screen (as it makes things rather tedious), they also don’t want major jumps in the story, coupled with characters simply explaining away the missing pieces. Even if your show deals with time travel, you don’t get a pass on showing the audience how events unfold.

2. Moffat cannot successfully sustain a long story arc.

One of the most infuriating things about Sherlock is that a season only lasts three measly episodes. And, considering the rising stars of Cumberbatch and Freeman, who knows how much time the pair will have in the future to devote to season four. But, when looking at Moffat’s track record with Doctor Who, and its significantly longer seasons, perhaps Sherlock fans should look on the shortened length their show’s season as a blessing.

Both Who and Sherlock operate in similar manners. Each contains a set of stand-alone episodes that coalesce under the banner of a longer arc. While this works excellently with Sherlock, having the final season end game hinted at over the course of the three episodes (or, sometimes having it revealed in the season finale that a particular character has had his or her hand in things for some time), with Who, each arc sputters along in a bit of a muddled mess with the writers seeming to make up the rules as it goes along.

Now, I certainly believe that Moffat sits down and charts an arc for Doctor Who at the start of each season. After all, not to do so on a series that involves traversing time and space would be pretty foolish. And while viewers don’t want to see each minute beat of the arc played out clearly on screen (as it makes things rather tedious), they also don’t want major jumps in the story, coupled with characters simply explaining away the missing pieces. Even if your show deals with time travel, you don’t get a pass on showing the audience how events unfold.

When watching a season of Sherlock, you can sit back at the end of the finale and piece together the major season arc (and, at the end of each episode you can do the same with the episode arc). It’s not so clearly telegraphed that you can anticipate what’s to come (a frequent pitfall in a mystery), but there are enough threads to tie the story back together. It’s smart and well-constructed storytelling.

When watching Who, you can get to the end of a season and have no real understanding of what actually happened. I’m still trying to piece together everything that we found out about Clara and her moniker as the “Impossible Girl” (not to mention how the 50th Anniversary Special- as good as it was- failed to actually link to the previous episode in any way aside from showing us the War Doctor). Too often, the show relies on the nature of time travel to explain away inconsistencies (or, simply ignore anything that might be true about time travel to allow other event to happen). It’s sloppy and often lazy storytelling.

If Moffat is constructing a limited arc for Who, it is often excellent (see the “Silence in the Library” storyline as an example of a wonderful, but brief, arc). But when he is called upon to put together an arc over 10 or more episodes, the story falls apart and becomes embroiled in broken story threads and confusing story jumps. With Moffat, less is most certainly more.

When watching a season of Sherlock, you can sit back at the end of the finale and piece together the major season arc (and, at the end of each episode you can do the same with the episode arc). It’s not so clearly telegraphed that you can anticipate what’s to come (a frequent pitfall in a mystery), but there are enough threads to tie the story back together. It’s smart and well-constructed storytelling.

When watching Who, you can get to the end of a season and have no real understanding of what actually happened. I’m still trying to piece together everything that we found out about Clara and her moniker as the “Impossible Girl” (not to mention how the 50th Anniversary Special- as good as it was- failed to actually link to the previous episode in any way aside from showing us the War Doctor). Too often, the show relies on the nature of time travel to explain away inconsistencies (or, simply ignore anything that might be true about time travel to allow other event to happen). It’s sloppy and often lazy storytelling.

If Moffat is constructing a limited arc for Who, it is often excellent (see the “Silence in the Library” storyline as an example of a wonderful, but brief, arc). But when he is called upon to put together an arc over 10 or more episodes, the story falls apart and becomes embroiled in broken story threads and confusing story jumps. With Moffat, less is most certainly more.

3. Moffat needs a co-showrunner.

This is the most important of the three elements I came up with when pondering the success of Sherlock versus the disappointment of Who. On Sherlock, Moffat works alongside co-creator Mark Gatiss (who also portrays Mycroft Holmes on the series), while Moffat has spent most of his tenure as the sole showrunner for Who (there have been additional executive producers on the show during this time, but Moffat has been the true showrunner).

Now, it’s a herculean task to be a showrunner of one show, much less have two under your control (even if one only films every other year), so I do have sympathy for the massive undertaking Moffat is attempting. But, that doesn’t mean that I can excuse how poorly Who has fared during his time at the helm.

When Moffat speaks of his work crafting the story arcs for Sherlock, he discusses how he and Gatiss sit together to create the stories. The collaborative aspect of such a set-up almost certainly fosters the stronger storylines while allowing for the dismissal of the weaker options. While there is a team of writers working on Who, Moffat is charged with being the central voice in crafting the season long arcs and assigning the individual episodes to the writing staff. Being responsible for arcs of ten or more episodes each year is a great amount of content to craft and a great deal of story for one person to be in charge of.

3. Moffat needs a co-showrunner.

This is the most important of the three elements I came up with when pondering the success of Sherlock versus the disappointment of Who. On Sherlock, Moffat works alongside co-creator Mark Gatiss (who also portrays Mycroft Holmes on the series), while Moffat has spent most of his tenure as the sole showrunner for Who (there have been additional executive producers on the show during this time, but Moffat has been the true showrunner).

Now, it’s a herculean task to be a showrunner of one show, much less have two under your control (even if one only films every other year), so I do have sympathy for the massive undertaking Moffat is attempting. But, that doesn’t mean that I can excuse how poorly Who has fared during his time at the helm.

When Moffat speaks of his work crafting the story arcs for Sherlock, he discusses how he and Gatiss sit together to create the stories. The collaborative aspect of such a set-up almost certainly fosters the stronger storylines while allowing for the dismissal of the weaker options. While there is a team of writers working on Who, Moffat is charged with being the central voice in crafting the season long arcs and assigning the individual episodes to the writing staff. Being responsible for arcs of ten or more episodes each year is a great amount of content to craft and a great deal of story for one person to be in charge of.

Having a writing partner (it should be noted that Moffat and Gatiss are the sole authors or co-writers of every Sherlock episode) undoubtedly makes putting together a complex series like Sherlock leagues easier than it would be alone. With a producing partner alongside you every step of the way, each idea is vetted by someone with the same ranking in the production. Presumably, there have been disastrous Sherlock ideas that have fallen by the wayside due, in part, to the roles Gatiss and Moffat play in the writing process.

With Who, Moffat is ostensibly the final creative word on the story. The writers create the individual scripts (Moffat only occasionally writes Who episodes now), and pass them onto Moffat for a final pass. Now, I could be off base, and there might be a major meeting on every script to discuss the storyline and how the particular episode features into the larger season arc. However, the Who writing process has been detailed in several interviews as having a script assigned to a writer, who writes it and turns it in to Moffat (unlike in many US productions, there isn’t a true “writers’ room” where stories are “broken” with the entire writing staff present).

Now, one might ask, why is this such an issue for the Moffat era of Who? After all, Russell T. Davies operated with a similar set-up when he ran Who. I think the major difference is in Moffat’s past television experience (or, lack thereof). Davies had been the showrunner for the British version of Queer as Folk prior to launching Who, so he had past experience running a popular and complex series. Moffat, while having previous television experience, didn’t have that same background.

No matter what the reasoning behind Moffat’s inability to successfully manage a television series on his own, it is clear that when he is teamed with a co-showrunner, the show runs smoothly. Sherlock’s success is the result of many elements working well together, but at its heart is the strong storylines and great writing- all attributable to the collaboration between Moffat and Gatiss.

Having a writing partner (it should be noted that Moffat and Gatiss are the sole authors or co-writers of every Sherlock episode) undoubtedly makes putting together a complex series like Sherlock leagues easier than it would be alone. With a producing partner alongside you every step of the way, each idea is vetted by someone with the same ranking in the production. Presumably, there have been disastrous Sherlock ideas that have fallen by the wayside due, in part, to the roles Gatiss and Moffat play in the writing process.

With Who, Moffat is ostensibly the final creative word on the story. The writers create the individual scripts (Moffat only occasionally writes Who episodes now), and pass them onto Moffat for a final pass. Now, I could be off base, and there might be a major meeting on every script to discuss the storyline and how the particular episode features into the larger season arc. However, the Who writing process has been detailed in several interviews as having a script assigned to a writer, who writes it and turns it in to Moffat (unlike in many US productions, there isn’t a true “writers’ room” where stories are “broken” with the entire writing staff present).

Now, one might ask, why is this such an issue for the Moffat era of Who? After all, Russell T. Davies operated with a similar set-up when he ran Who. I think the major difference is in Moffat’s past television experience (or, lack thereof). Davies had been the showrunner for the British version of Queer as Folk prior to launching Who, so he had past experience running a popular and complex series. Moffat, while having previous television experience, didn’t have that same background.

No matter what the reasoning behind Moffat’s inability to successfully manage a television series on his own, it is clear that when he is teamed with a co-showrunner, the show runs smoothly. Sherlock’s success is the result of many elements working well together, but at its heart is the strong storylines and great writing- all attributable to the collaboration between Moffat and Gatiss.

Having explored these three elements, there is most certainly hope that Who can rebound into a series that is similar in quality to Sherlock. While shortening the Who season is absolutely not going to happen (and, honestly, it shouldn’t have to happen- plenty of shows are able to sustain a complex narrative over the span of 10-13 episodes), there have been rumors regarding the BBC bringing in a co-showrunner for the series. As for the issue of Moffat’s lost female characters, with the advent of Mary on Sherlock, it’s become clear that Moffat (when combined with Gatiss) is able to produce an interesting, complex, and self-sufficient female character who doesn’t need a man to survive in the world.

I’m not entirely sure Who will truly be able to rebound under the control of Moffat (reports have indicated that he may be looking to step down from the show after this upcoming season). But I remain hopeful that positive steps can and will be taken to make it more watchable. But, until I see that change, I will continue to warn Sherlock fans away from the recent seasons of Who, while continuing my recent campaign to get everyone I know to watch Sherlock.

Having explored these three elements, there is most certainly hope that Who can rebound into a series that is similar in quality to Sherlock. While shortening the Who season is absolutely not going to happen (and, honestly, it shouldn’t have to happen- plenty of shows are able to sustain a complex narrative over the span of 10-13 episodes), there have been rumors regarding the BBC bringing in a co-showrunner for the series. As for the issue of Moffat’s lost female characters, with the advent of Mary on Sherlock, it’s become clear that Moffat (when combined with Gatiss) is able to produce an interesting, complex, and self-sufficient female character who doesn’t need a man to survive in the world.

I’m not entirely sure Who will truly be able to rebound under the control of Moffat (reports have indicated that he may be looking to step down from the show after this upcoming season). But I remain hopeful that positive steps can and will be taken to make it more watchable. But, until I see that change, I will continue to warn Sherlock fans away from the recent seasons of Who, while continuing my recent campaign to get everyone I know to watch Sherlock.