This week’s movie releases were The Dilemma and The Green Hornet. As can be expected in the films of the early new year, they were critically vilified. The first I actually enjoyed, contrary to the opinions of most critics it seems. Where it may have been bi-polar in terms of its tone, I got enough out of it to justify the view. The second film has no appeal to me at all; I just thought it looked bad. Yes, I’m guilty of the that sin of judging books by their cover (films by their trailer), but it doesn’t look like much has come up to vindicate the movie of my skepticism. I’ll watch it at a friend’s house if he’s Redboxed it, and if I have nothing better to do.

My first reaction for this week’s LTTT column was to do The Dilemma and recommend a similarly themed but much better executed film in Mike Nichol’s Closer. That would be all well and good, except that I’ve already recommended that movie in a previous column. It is one of my absolute favorite films of the last decade, and I jump on every chance I get to pimp it. (So watch it if you haven’t!) Other films Ron Howard’s latest reminded me of I didn’t feel particularly compelled to recommend or seemed tied to the film only very loosely. What’s a guy to do? Seems kind of absurd to recommend Apollo 13 just because Ron Howard directed The Dilemma (though it is a solid movie).

I’ve decided to make this the first article in a series; a series whose entries will appear in these unique situations where the releases of the week are not worth commenting on further or preclude me from giving a recommendation that I’d like. Basically, I will spotlight a favorite film of my own. This allows me to continue the goal of recommending good cinema, instead of half-heartedly saying “hey, you liked The Dilemma with Kevin James? Check out Paul Blart: Mall Cop.” It’ll allow me to give you better recommendations and have more fun while doing so.

So, without further ado, my first selection is 1977’s Saturday Night Fever, directed by John Badham. It’s my favorite film of the 1970’s, no small praise for a decade which contains cinematic big-hitters like The Godfather, Annie Hall, Rocky, Taxi Driver, Star Wars, Jaws, and Apocalyse Now. It was also selected in 2010 for the National Film Registry because it’s “culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant.”

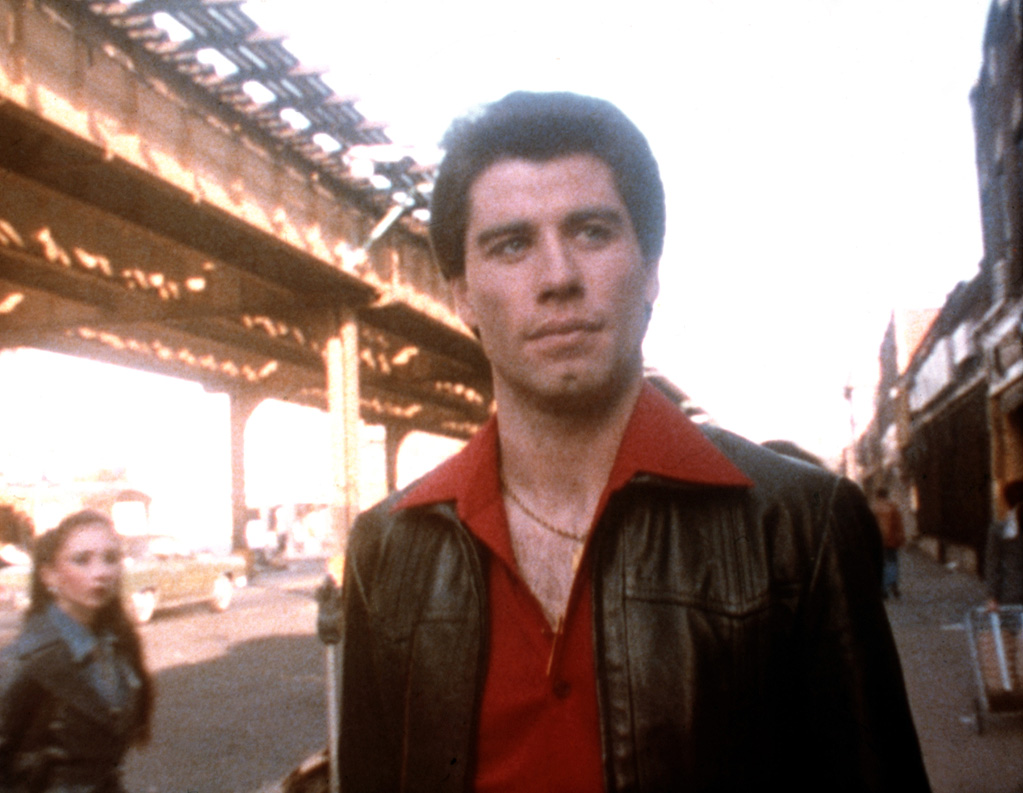

The film starts with one of the most iconic and recognized scenes in movies: Tony Manero’s (John Travolta) strut down the streets of Brooklyn to the tune of “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees. Three seconds into the film we are pulled in, and without any words Badham has made the audience like Tony - he has rhythm, style, confidence - which is good because we’ll need that to insulate us against his later actions. His life philosophy is summed up early on as he tries to get an advance from his boss at the paint store where he works:

“Pay day’s Monday,” Mr. Fusco says.

Tony’s agitated. “I know pay day is Monday, but everywhere else it’s Friday and Saturday.”

“Yeah, and by Monday it’s gone, wasted on boozing and whoring. This way you get paid on Monday, you got money all week. You can save a little, build for a future.”

“Oh fuck the future,” Tony says. Succinct, simple words to live by. He lives in the now.

Tony’s 19 years old. He is a nobody during the day and during the week, even his family thinks he’s a loser, but a he’s god on the dance floor Saturday nights at 2001, the local disco. His group of friends, Joey, Double J, Gus, and Bobby C, are as immature and not as talented. They live to drink, smoke, and lay. They are all profane, racist, misogynistic, and homophobic. Even though Tony’s talent on the dance floor could provide a means to a more meaningful existence, currently he is headed down a path to self-destruction and mediocrity.

Tony’s opportunities for change and love hinge on a dance contest that 2001 is hosting. On one of his Saturday nights, he sees Stephanie Mangano (Karen Lynn Gorney). Her no-bullshit approach is foreign to Tony, who’s used to having women fling themselves at him. Stephanie paves the way for Tony to escape from his dead end life and make something of himself.

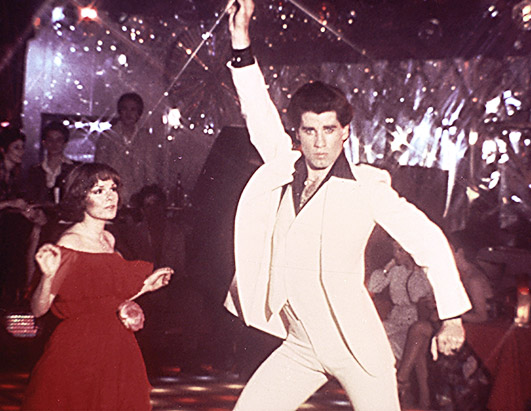

Most people who have some distance between now and their last viewing tend to remember the dance sequences, Tony’s talent, the white polyester suit, but the film really has more to offer than that. The world around these characters is dirty, violent, and very dark at times. The relationship between Tony and Stephanie is far from perfect, and one of my favorite things about the film. He’s incredibly immature, and Stephanie is a wannabe elitist. She works in Manhattan and brags about meeting Joe Namath and Laurence Olivier in her high-class office building. She tries hard to mask her Brooklyn accent and improper English, and is condescending to Tony about his life. This is perfectly exemplified in a scene at a diner after Tony has finally convinced her to have coffee with him. Their food says something about each of the characters Tony orders a cheeseburger, which he promptly pigs out on, and she has just tea with lemon, because “it’s a lot more refined.”

“Would you like to know what I do?” he asks.

“That’s not necessary...”

“I work in a paint store, (mouth full of burger) and I got a raise this week-”

She cuts him off. “You work in a paint store? Let me guess, you live with your parents, you work all week then blow it all off at 2001, right? You’re a cliche. You’re nowhere, on your way to no place.”

Her words sting. She’s harsh, and condescending beyond all doubt, but her words have truth. She challenges Tony, and they ground each other. They are two imperfect people, trying to be better.

Moments like those above resonate with me just as well as the well-choreographed dance scenes. I relate to Tony’s longing for a place that represents a better life, in his case Manhattan, and love the ways Badham and screenwriter Norman Wexler convey that to us. There’s a beautiful scene that takes place on a bench next to that iconic bridge, and Tony is able to relate every detail about it, because it’s what eventually will take him to the better life he envisions for himself. He knows the length, the height, how many cars go across it annually, and even that a guy fell into wet cement and died there. A very well done piece of writing.

All this talk about the characterization is not meant to slight the famous dance scenes, which are famous for very good reason. What it is meant to do though is suggest that nobody would care about the dance scenes without all this other good stuff, and that they are there to supplement the characters. Tony’s dance in the middle of the film shows us how exactly he got his reputation at the club, and that he is in fact very talented. His and Stephanie’s dance at the end to “More Than A Woman” by the Bee Gees is the culmination of their romantic relationship and set up the final sequence that forces Tony to change.

There’s a reason this movie is still remembered thirty years from its making. Step Up has some excellent dancing in it, but nobody will remember it in 2040. Saturday Night Fever is not a perfect film by any means, but it profoundly captures what it’s like emotionally to be young, while quelling our hunger for something we’ve never seen before. For that, I love it.